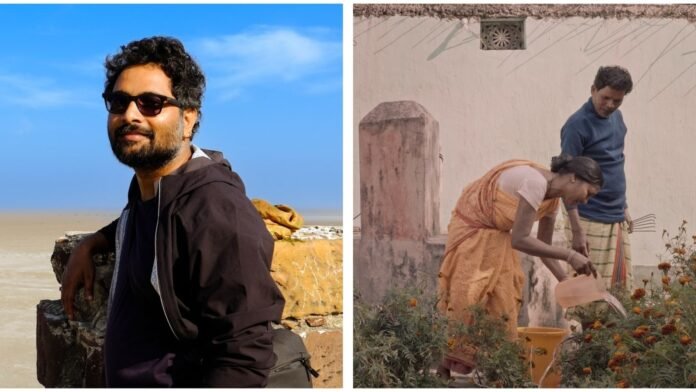

In Tortoise Under The Earth (Dharti Latar Re Horo, in the Santhali language), Shishir Jha’s striking feature film set in Jharkhand, we see a nameless tribal couple, played by Jagarnath Baskey and Mugli Baskey, as they recount a life lived by: through grief, perseverance and hope. Their personal loss is intermingled with a wider loss of identity and how they are being forced to shift because of the mining of uranium. A cinéma vérité approach gradually interweaves elements of anthropological aspects of their everyday existence.

In an exclusive interview with Hindustan Times, director Shishir Jha opened up about the process of making the film, which was a combination of organic process as well as intentional narrative choices. (Also read: Dahomey review: Mati Diop’s probing documentary on restitution of stolen artefacts makes for essential viewing)

So much of the journey of the two people in the film feels as if they are drawn from their reality, from their own experiences. When did you meet them first, and how did this collaboration come about?

The story is based on the events, experiences that have happened in their lives, as well as the people and the stories of them surrounding them. It is a collection of all these things, some real, some fiction. It is a hybrid of sorts, a mix of both worlds.

I was with them for around a year or so. For the first two months, I simply stayed around the place where I did not know their language. It was quite an intuitive approach… I had done a workshop in Cuba in Spanish with Abbas Kiarostami [acclaimed Iranian film director and screenwriter], and even there, I did not know the language. So, in a similar way, I approached cinema as well, visually and tracing the emotion. That was a satisfying process for me, and I wanted to create a space like that for more of such experiences. So the experience I had in Jharkhand is an extended form of that.

One of the fascinating aspects of the film is also how the mythical aspect is balanced with the hard reality of degradation of the land in which these two people are residing. How did you find that balance in the two elements?

It was extremely organic. I did not want to have a hard-set script for such an issue and did not want to approach it in a conventional manner. It takes a lot of resources when you imagine and write about something like this… one has to build around it, and we did not have that leverage. So it was very organic in the manner in which these issues came up. These issues are real. Be it the mythology, folk stories, it is all there in the way the people talk about it. They were also excited to share these things, and it was like an exchange of stories and cultures when I reached the community. It became ingrained in the film in this manner.

Even the pictures of their family are completely real. When we talk about history, belongingness, one’s roots and memories, those pictures are able to capture those things. It is very important in the context of what we are erasing, what we are extracting… We are not simply extracting the materials but… so much more.

How were you able to navigate with the actors in this case because there is a continuous play between what is fiction and what is truth…

All the events are real. We had two characters, and to tell the story, the concern was not that all the events had to be around them. It happened to someone else but we created a kind of hybrid fiction to show as if this is happening with them.

In a similar way I was not aware that uranium extraction was happening there. I was not keen on making a film on mining. In Jharkhand, a lot of people are affected by this issue and if one is not including this reality in the film… to me it is nothing less than cheating with those people. It is very much a part of their lives, it is affecting their lives.

The first half of the film is about community and towards the end this sense of community expands to only reflect on how it is also growing apart in a way…

It was intentional. I wanted to show that if someone wants to know another person, then there has to be a sense of their traditions, history and culture, or else there will be no connect. I did not want to tell this story in an informative fashion and wanted to create a sort of emotional connect with these people and understand why they are doing certain things. All their songs, their culture, even for me was like a celebration. How minimal and beautiful it is! I thought of bringing the same effect to the people who would be watching.

Tortoise Under The Earth is such a great example of independent filmmaking. In India, there are challenges in terms of distribution and proper support to independent films. What are your thoughts in this regard?

Film is an expensive medium. But the experience of independent filmmaking allows so much creative freedom. It is not essential that one has to always take the monetary point of view into account, but for me what is more important is the creative point of view. It is my decision how I want to keep my film, and along with that artistic expression comes the problem of not following the conventions. So most of the OTT platforms and distributions will not be there because they are afraid of backing and supporting it.

I am so happy that Mubi is a platform which gives space for these stories that express and share your work. To take the film to the right audience it is very important. That your work reaches the right platform. There are so many types of films, experimental ones and documentaries, these options that Mubi provides are so important.

Tortoise Under The Earth is available to watch on Mubi.