A pattern of encroaching and retreating ice sheets during and between ice ages has been shown to match certain orbital parameters of Earth around the sun, leading to researchers being able to predict that the next ice age will take place 10,000 years from now.

“The pattern we found is so reproducible that we were able to make an accurate prediction of when each interglacial period of the past million years or so would occur and how long each would last,” said Stephen Barker of Cardiff University in Wales, who led the study, in a statement. “This is important because it confirms the natural climate change cycles we observe on Earth over tens of thousands of years are largely predictable and not random or chaotic.”

However, don’t rush for your woolly hat and scarf just yet, because the long-term effects of human-made climate change could prevent the next ice age from ever happening.

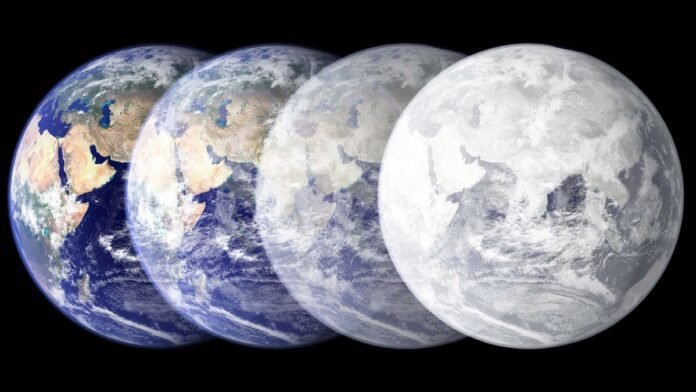

Our planet has always undergone cycles of warm and cold, ice ages and interglacials. These cycles are quite separate from human-induced climate change, which is well documented, incontrovertible and is largely overriding Earth’s natural climate cycles.

Related: How many ice ages has the Earth had, and could humans live through one?

Those natural cycles are caused by changes in three properties of Earth and its orbit around the sun. Together, they are referred to as Milankovitch cycles, after the early 20th century Serbian physicist Milutin Milankovitch.

The key players in these cycles are Earth’s obliquity, the precession of its rotational axis and the shape of Earth’s orbit around the sun.

Obliquity refers to Earth’s tilt. Imagine drawing a straight line through Earth, along its rotational axis around which the planet spins every 24 hours. The angle this line makes to the ecliptic plane, which is the plane of the solar system in which all the planets orbit, is the obliquity. Currently, Earth’s obliquity is 23.4 degrees, but over history it has varied between 22.1 and 24.5 degrees approximately every 40,000 years.

Precession refers to the “wobble” of this rotational axis. Let’s go back to that imaginary line extending through Earth’s rotational axis and picture ourselves looking down on one of Earth’s poles. Across a cycle of about 21,000 years, we would see that imaginary line draw out a circle. It is an effect analogous to a spinning top wobbling as it whirls around. Precession is why the Pole Star changes over time. Currently Earth’s rotational axis is pointed toward Polaris in Ursa Minor, but in the past it has pointed at different stars, and will do so again in the future.

Finally, the shape of Earth’s orbit can change slightly, from more elongated to less elongated (our average distance from the sun doesn’t change). This can lead to Earth’s orbit precessing around the sun. Currently, southern hemisphere summer takes place when Earth is at its closest point to the sun and northern hemisphere summer takes place when Earth is farther away. However, this changes, with two cycles of periods of 100,000 and 400,000 years. In the future, northern hemisphere summer will take place when Earth is closer to the sun, as Earth’s orbital elongation, or eccentricity, varies.

The Milankovitch cycles are all caused by the combined gravitational effects of the sun, Jupiter and to a lesser extent the other planets acting on Earth. That the Milankovitch cycles cause climate variations is not controversial, but matching specific effects to either glaciations or the onset of interglacials has been tricky because it is difficult to accurately date when these happened in the geological record going back millions of years.

However, the new research has modeled a million-year record of ice sheets and deep ocean temperatures with a fidelity good enough to start matching them to specific phases in the Milankovitch cycles.

“We found a predictable pattern over the past million years for the timing of when the Earth’s climate changes between glacial ‘ice ages’ and mild warm periods like today, called interglacials,” said paleoclimatologist Lorraine Lisiecki, who is a professor of the University of California, Santa Barbara and a member of Barker’s team.

“We were amazed to find such a clear imprint of the different orbital parameters on the climate record,” said Barker. “It is quite hard to believe that the pattern has not been seen before.”

Specifically, they found that the end of any given ice age, the last of which was 11,700 years ago, is brought about by a combination of changes in precession of Earth’s axis, which affects peak summer heating in the northern hemisphere, and variances in obliquity, which affects the total solar energy received at high latitudes.

They also discovered that obliquity seems to be the sole driver behind starting a new ice age.

With this knowledge, Barker’s team predicted that the next ice age would ordinarily take place in 10,000 years’ time.

Related: An interstellar cloud may have caused an ice age on Earth. Here’s how

However, the effects of human-made climate change will be so long-lasting that they could prevent the next ice age from ever happening.

“Such a transition to a glacial state in 10,000 years’ time is very unlikely to happen because human emissions of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere have already diverted the climate from its natural course, with longer-term impacts into the future,” said Gregor Knorr of the Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research in Germany.

The predictability of the pattern that Barker’s team found allows them to generate a baseline of how Earth’s long-term climate would unfold over the next 20,000 years if human-made greenhouse emissions were not a factor. The next step is to look at how human-made climate change is deviating from that baseline so that the effects of industrial global warming long into the future can be better quantified.

“Now that we know that climate is largely predictable over these long timescales, we can actually use past changes to inform us about what could happen in the future,” said Barker. “This is vital for better informing decisions we make now about greenhouse gas emissions, which will determine future climate changes.”

The findings were published on Feb. 28 in the journal Science.