By Andy Tomaswick

March 14, 2025

X-ray astronomy is a somewhat neglected corner of the more general field of astronomy. The biggest names in telescopes, like Hubble and James Webb, don’t even touch that bandwidth. And Chandra, the most capable space-based X-ray observatory to date, is far less well-known. However, some of the most interesting phenomena in the universe can only be truly understood through X-rays, and it’s a shame that the discipline doesn’t garner more attention. Kimberly Weaver of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center hopes to change that perception as she works on a NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC) grant to develop an in-space X-ray interferometer that could allow us to see for the first time what causes the power behind supermassive black holes.

Chandra has been a workhorse for decades. Initially launched in 1999, it has collected plenty of X-ray data on all sorts of objects throughout the universe. But, its hardware at this point is more than 25 years old, and there have been massive improvements in the sensitivity of X-ray equipment in that time. It is also planned to be wound down due to NASA budget cuts by 2029.

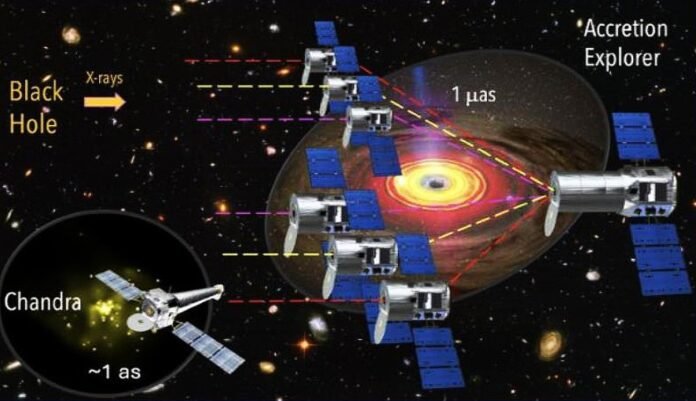

But one thing Chandra can’t do is take interferometry data. It has two instruments—the Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer and the High-Resolution camera—primarily responsible for capturing its X-ray images. However, it is limited to about .5-1 arcsecond of the resolution, which makes teasing out details about massive objects millions of light years away, like supermassive black holes, challenging, to say the least.

Fraser discusses how an in-space interferometer would work – just in a different bandwidth than the NIAC proposal.

The Accretion Explorer (AE) project proposed by Dr Weaver takes an entirely different approach. According to a press release from NIAC, the Phase I study “will focus on a large free-flying X-ray interferometer.”

Interferometers are probably most famous for the first detection of gravitational waves in 2016. The idea behind the AE takes the concept from the Laser Interferometer Graviational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and scales it up to space—but with X-rays. And there will be more than just the two lines that comprise LIGO.

The AE would have several mirrorcraft floating independently from a mothercraft with a detector. Their precise positioning, compared to one another and the mother craft, is absolutely critical to the mission’s success. When an X-ray hits one of the separate mirror craft, the mirror on it is positioned to bounce the X-ray back to the detector craft. If enough of these mirror craft are pointed at and X-rays are detected from the same direction, each connection between them and the larger detector craft would work as a “baseline” of the interferometer.

As part of the Phase I grant, Dr. Weaver and her team will determine how to optimize the mirror positioning and technical details like what kind of detector sensitivity would be necessary to differentiate particular X-ray energies crucial to understanding mega-objects like supermassive black holes.

Brief video showing how interferometry works.

Credit – INFN YouTube Channel

Some underlying technologies, like the exact positioning techniques and stable control methods that would keep the system working in lockstep, could be helpful outside this one space project. However, given the massive distances between the different baseline parts, it’s unclear how useful they would be back on Earth. But, if NIAC is good at anything, it’s supporting crazy ideas that happen to become viable projects later in their development cycle. Maybe this time, they’ll even be able to push X-ray astronomy into the limelight.

Learn More:

NASA / Kimberly Weaver – Beholding Black Hole Power with the Accretion Explorer Interferometer

UT – Half the Entire Sky, Seen in X-Rays

UT – A CubeSat Mission Will Detect X-rays from GRBs and Black-Hole Mergers

UT – X-Ray Telescopes Could Study Exoplanets Too