A construction project in Southeast Asia dredged up the remains of the extinct human relative Homo erectus from the seabed. The discovery, described in four studies in the June Quaternary Environments and Humans, reveals a lost landscape, long since submerged, where hominids lived by a river and hunted buffalo and turtles.

The first hominids known to have left Africa, about 1.8 million years ago, H. erectus traveled east to what is today the island of Java, Indonesia, and survived there until perhaps 108,000 years ago. Though archaeologists have made discoveries from submerged lands elsewhere, this is the first time hominid remains have been recovered from this region’s seabeds.

This is “one of the most interesting unknowns in the world story,” says archaeologist Geoff Bailey at the University of York in England, who was not involved in the work. The region was home to H. erectus for hundreds of thousands of years. Later it may have been home to Denisovans or other hominids. “It was also the stepping-off point for human movement into Australia and New Guinea,” Bailey says. “This is a place where we ought to be focusing this sort of underwater investigation.”

Harold Berghuis, a geologist now at Leiden University in the Netherlands, had reason to think the seabed might hold secrets. He has consulted for years on dredging projects near a major port city on Java. From 2014 to 2015, he was involved in a project to create an artificial island with sand dredged from the Madura Strait, which divides Java from neighboring Madura.

“I knew beforehand there might be fossil material,” Berghuis says. Over the last million years, sea level changes have at times exposed huge areas of land in the region: much of Indonesia was connected to mainland Asia, part of a lost region called Sundaland. The Madura Strait, Berghuis knew, was once dry land.

From 2015 to 2018, Berghuis scoured the artificial island’s one square kilometer of open sand. “It’s like you’re in the Sahara,” he says. He explored alone, on his hands and knees, collecting 6,372 fossils. After initially storing these in his office, Berghuis gave them to the Bandung Geological Museum on Java. Curator Unggul Prasetyo Wibowo calls the discovery “fortunate” and says the museum plans to display the collection.

Geologic data collected during construction campaigns, including cores drilled into the Madura Strait seabed, enabled Berghuis to computationally reconstruct the submerged landscape, revealing a plain with a river running through it.

He teamed up with researchers at multiple universities to explore the finds. They dated the fossils and surrounding sediments to between 131,000 and 146,000 years ago with a technique that reveals the last time they were exposed to sunlight.

Among the fossils were two fragments of hominid skull, both less than 50 millimeters across. Based on comparisons with other fossils, Berghuis and his colleagues concluded that they belonged to H. erectus.

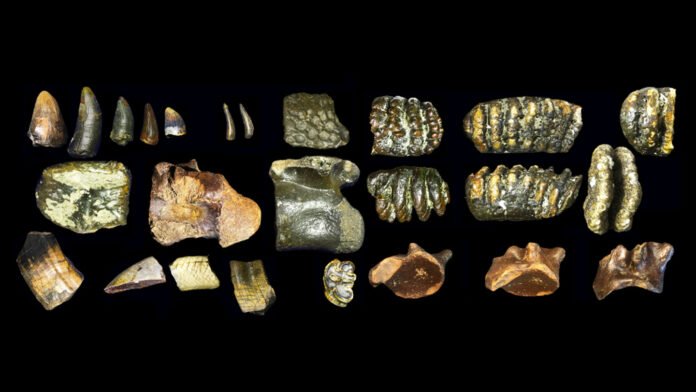

The animal fossils revealed a thriving ecosystem in and around the river, including turtles, pythons and sharks. Large mammals including buffalo, hippopotamus-like Hexaprotodon and elephant-like Stegodon roamed the lowlands.

Some of the turtle and mammal bones have cut marks or fractures, respectively, suggesting H. erectus hunted them, and in the mammals’ case extracted bone marrow. Meanwhile, cow-like remains are dominated by young and healthy adults, suggesting the hominids were targeting those individuals.

Plenty of unknowns remain. The animal fossils imply this region’s H. erectus had more advanced hunting skills than those dwelling elsewhere — either developed independently, or perhaps learned from other Asian hominids such as Denisovans, if H. erectus met them.

It’s notable that Berghuis didn’t find recognizable stone tools, says Silvia Bello at London’s Natural History Museum, who edited the papers and coauthored an introduction to them. This could suggest H. erectus used alternative tools, “maybe bamboo or shells, which did not preserve,” Bello says.

These mysteries highlight the importance of exploring the submerged landscapes of Sundaland, Bailey says.

Source link