Members of New Mexico’s Picuris Pueblo Tribal Nation have long told stories about having descended from ancient North American ancestors.

Genetic evidence now backs up what Picuris people — but not archaeologists — knew all along and fleshes out lost pieces of the tribe’s past. The new results, published April 30 in Nature, came out of a collaborative study between Picuris Pueblo representatives and scientists.

Traditional knowledge keepers at Picuris Pueblo describe ancestral and cultural connections to ancient pueblo sites in northwestern New Mexico. Oral histories emphasize ties to Chaco Canyon society, a regional network of over 200 Great House communities that flourished from about 850 to 1150. Chaco Canyon lies 275 kilometers west of Picuris Pueblo.

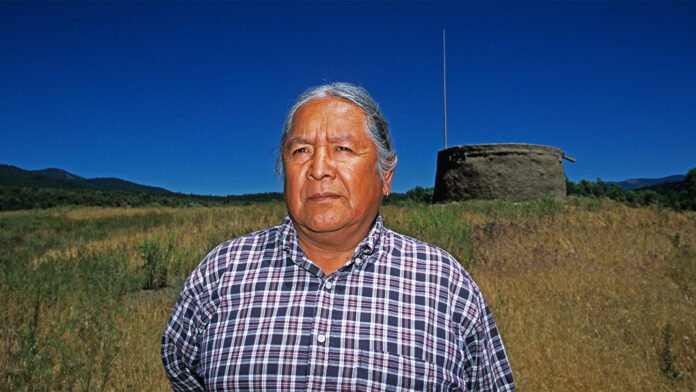

“Our elders knew we had always been here, but it was very moving and powerful to see it validated on paper that we have a maternal genetic link to Chaco Canyon,” said Craig Quanchello, Picuris Pueblo lieutenant governor and study coauthor, at an April 29 press briefing.

Frustrated that their objections to oil and gas drilling in Chaco Canyon were being ignored, Picuris officials asked University of Copenhagen evolutionary geneticist Eske Willerslev to fill in gaps in their tribal history using genetic data. Willerslev had organized previous investigations of ancient North American DNA histories in modern Native Americans, including one showing close genetic ties between Kennewick Man’s 8,500-year-old skeleton and present-day Pacific Northwest tribes.

With tribal permission, Willerslev’s team analyzed DNA from 16 individuals buried 700 to 500 years ago at Picuris Pueblo. For comparison, 13 current tribal members provided blood samples. Additional DNA came from ancient and modern people in Siberia and the Americas, including individuals buried in the largest stone Great House in Chaco Canyon.

Ancient and modern Picuris show close genetic ties, including descent from a maternal Chaco Canyon line, the researchers say.

Some researchers have argued Chaco’s collapse around 1150 led to a full regional exodus. In that view, ancestors of Picuris and other Pueblo tribes arrived in the Four Corners region later. The new study undermines this idea.

Patterns of inherited gene variants among ancient Picuris indicate that their population remained stable, at roughly 3,000 individuals, after the abandonment of Chaco Great House settlements. That stability indicates that enough Picuris ancestors remained in the region once the Chaco era ended to maintain a line of descent that led to present-day Picuris, the researchers say. Only Picuris remains dated to after 1535 showed DNA from Athabascan people, a population that possibly entered the U.S. Southwest by around 1450, they add.

Genetic analyses in the new study suggest Picuris numbers dropped about 85 percent after Spanish colonial rule began in the mid-1500s, Willerslev’s group says. Quanchello notes that Picuris Pueblo people currently number 306.

Pueblo tribes throughout the Southwest United States claim connections, so far genetically untested, to Chaco Canyon’s ancient people and culture.

A growing number of collaborations between scientists and Indigenous communities have found genetic signs of ancient North American ancestry among today’s Native American tribes. Indigenous groups’ insistence on reburying remains of their ancestors, initially resisted by archaeologists, largely inspired those projects. A 1990 federal law requiring repatriation of Native American artifacts and human remains, along with advances in DNA technology, increased pressure to link ancient skeletal finds to modern tribes.

Many Indigenous communities still harbor anger at archaeologists who demanded DNA samples from them and intruded on sacred burials. Ironically, genetic data now support oral histories and challenge archaeological assumptions about disconnected Native American cultures.

In a research area marred by controversy, the Picuris investigation “is a landmark project,” says archaeologist David Hurst Thomas of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Unlike many past studies, Picuris people recruited the scientists, keeping full control over participation and publication.

The new findings fit a scenario in which Pueblo communities such as Picuris left large Chaco settlements by around 1200 to escape a centralized political system with strict social classes, says Thomas, who was not part of Willerslev’s team. “Picuris downsized and moved to where they could make their own, smaller social networks.”

Source link