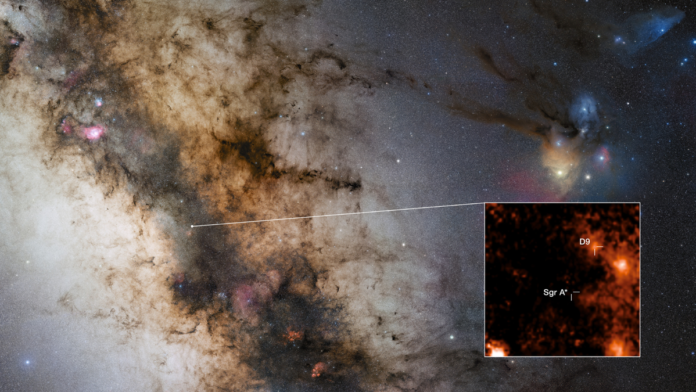

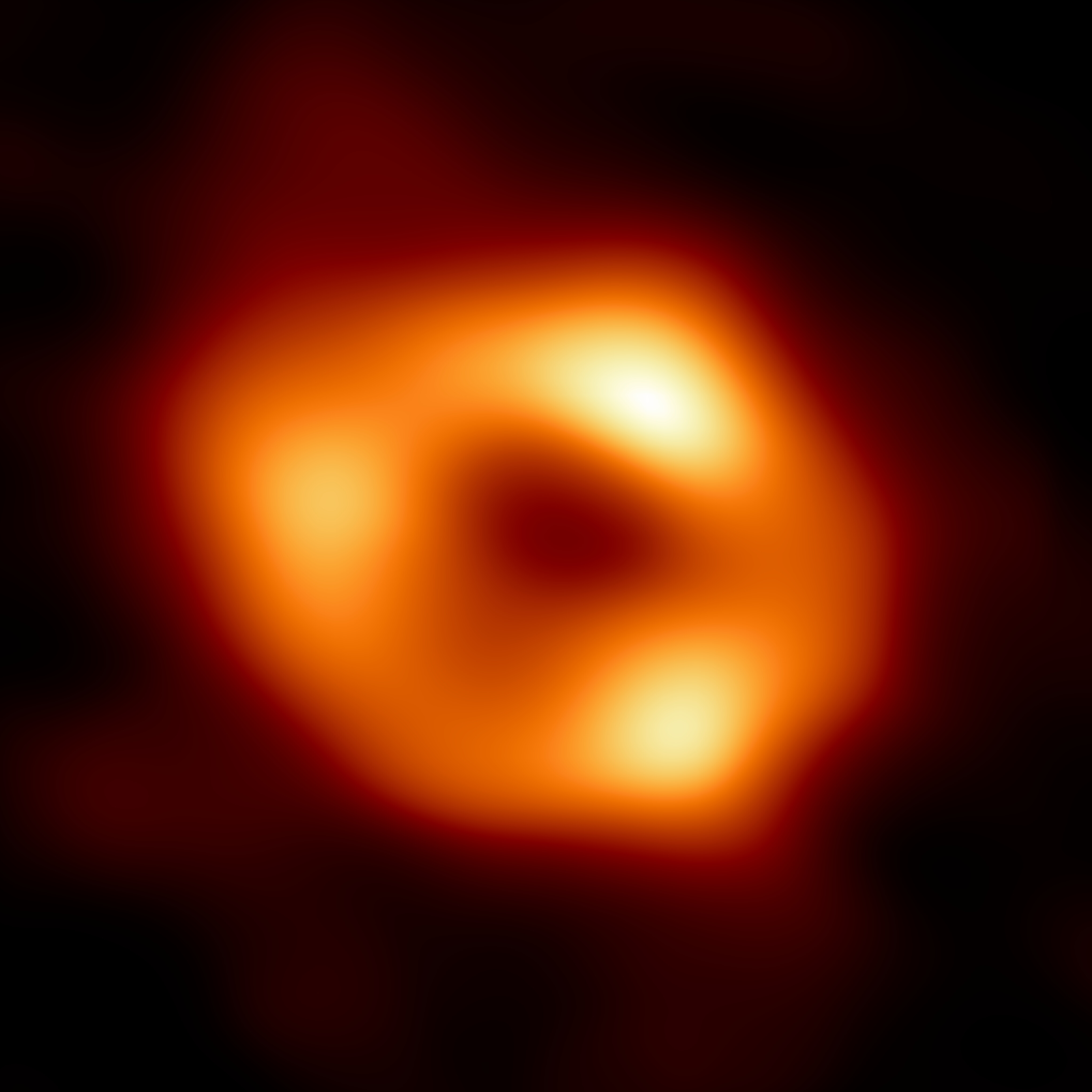

Astronomers have discovered the first binary stars orbiting a supermassive black hole. The stellar pairing in question orbits the cosmic titan at the heart of the Milky Way, Sagittarius A*.

The binary stars, designated D9, were found in data collected by the Very Large Telescope (VLT), located atop Cerro Paranal, an 8,645-foot-tall (2,635-meter) mountain in Chile’s Atacama Desert. By measuring their velocity, the team behind the discovery was surprised to find they were two stars, not one.

The fact that these binary stars so near Sgr A* have survived the tremendous gravity of this black hole indicates that these environments may actually be stable enough to allow for the birth of planets, the scientists behind this discovery say. “Black holes are not as destructive as we thought,” research lead author and University of Cologne scientist Florian Peißker said in a statement.

The team’s findings were published on Tuesday (Dec. 17) in the journal Nature Communications.

Let’s stick together…

Even though this discovery shows there may be more stability around supermassive black holes than previously suspected, the turbulent environment around Sgr A* means that although binaries can exist, these partnerships are probably fleeting.

The stars of D9 are estimated to be just 2.7 million years old, and while that may seem like an intimidatingly long time, considering the sun is an estimated 4.6 billion years old, it’s really just the blink of a cosmic eye.

Astronomers probably caught these stars at an opportune time. Eventually, the stars of D9 will be forced together, triggering a stellar merger.

“This provides only a brief window on cosmic timescales to observe such a binary system — and we succeeded!”, team member and University of Cologne researcher Emma Bordier said.

The discovery of such young stars around Sgr A* has told scientists something else new about these turbulent black hole-dominated environments, too.

Namely, the regions around supermassive black holes aren’t so chaotic that stars cannot be birthed there, as scientists had previously believed.

“The D9 system shows clear signs of the presence of gas and dust around the stars, which suggests that it could be a very young stellar system that must have formed in the vicinity of the supermassive black hole,” team member Michal Zajaček from Masaryk University and the University of Cologne said.

The D9 binary system exists within a fascinating group of stellar bodies called the S-star cluster. These stars whip around at incredible speeds thanks to the immense gravity of Sgr A*, which has a mass equivalent to that of around 4.3 million suns.

Arguably, the most intriguing objects in the S-cluster are bodies that appear like clouds of gas and dust but behave like stars called the “G objects.”

D9 was discovered as astronomers were attempting to discover what these the strange and “puffy” G objects actually are.

One current theory suggests that they may have once been binary stars like D9, which have been forced to merge, leaving a cloud of material surrounding other, as yet unmerged stars.

As such, the G objects may offer a glimpse of D9’s future.

The nature of objects around Sgr A* remains a mystery, but astronomers are diligently uncovering new clues.

The GRAVITY + upgrade to the VLT and the forthcoming Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) should make this picture even clearer in the future.

“Our discovery lets us speculate about the presence of planets since these are often formed around young stars,” Peißker concluded. ” It seems plausible that the detection of planets in the galactic center is just a matter of time.”