We see the Universe through a glass darkly, or more accurately, through a dusty window. Interstellar dust is scattered throughout the Milky Way, which limits our view depending on where we look. In some directions, the effects of dust are small, but in other regions the view is so dusty it’s called the Zone of Avoidance. Dust biases our view of the heavens, but fortunately a new study has created a detailed map of cosmic dust so we can better account for it.

The main problem with interstellar dust is that it doesn’t simply block all the light; it distorts light similar to other astrophysical effects. For example, dust tends to absorb blue colors more than red ones. So, if there is dust between us and a distant star the star will appear more red than it actually is. When you see a red star, does that mean it’s actually red, reddened by a relative motion away from us, or because there is dust in the way? It can be difficult to know the difference. Dust can also make distant galaxies appear dimmer than they actually are. Since we use the brightness of supernovae in a galaxy to determine its distance, dust can make galaxies appear more distant than they actually are.

We have long had a fairly good idea of where dust is in the galaxy, so we can account for many of these effects. But our understanding of the dust could be much better. Which is why this new study will be so beneficial.

The team started with data from the Gaia spacecraft, which has gathered observations of more than a billion stars in the Milky Way, including spectra observations of more than 220 million stars. They determined that about 130 million of the spectra observations would be useful in determining the distribution of galactic dust and so focused on them. One limitation of the Gaia spectra is that they aren’t high resolution. The main purpose of Gaia is to map the position and motion of stars, which doesn’t require a full spectrum to calculate. So the authors looked to data from the Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST), which has gathered high-resolution spectra from about 1% of the Gaia stars.

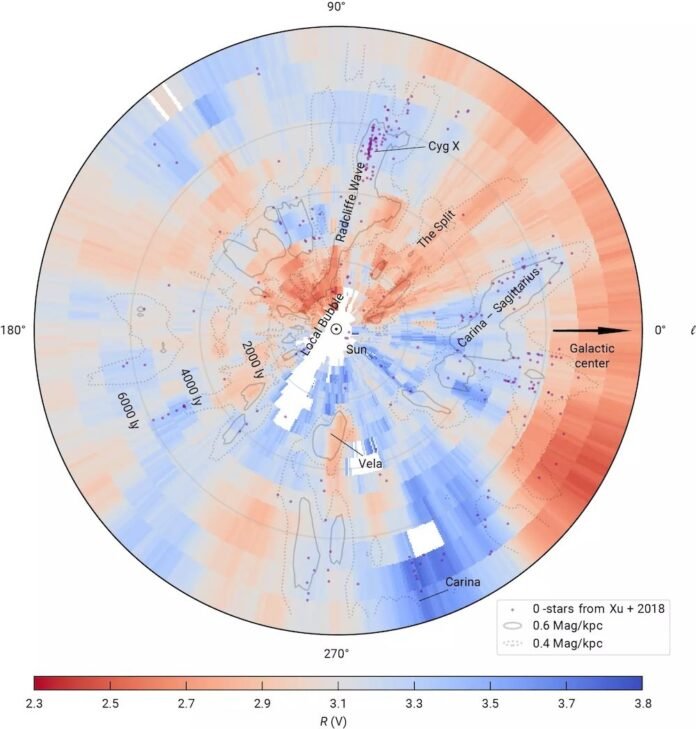

The next step was to use the LAMOST data to extrapolate spectra for the low-resolution Gaia spectra. Using machine learning and Bayesian statistics, the team could model a complete spectrum from a low-resolution one. From this, they could make a 3D map of galactic dust effects. Specifically, what is known as the extinction curve.

Since light at different frequencies is absorbed by dust at different rates, astronomers need to know not only how much dust there is in a particular direction, but also how different frequencies diminish with distance. This extinction curve can then be used to work backwards to determine the unbiased view. From their model, the authors created the most detailed extinction map of the Milky Way thus far.

They also found a surprising result. We known that the interstellar medium is composed of both gas and dust. Things such as neutral hydrogen and simple molecules don’t absorb much light compared to dust particles, so we assumed that dust grains were the primary cause of extinction curves. But when the team looked at particularly dense regions, they found the extinction curves didn’t flatten out as we expected. Instead, the curves became even more red-biased than less dense regions. This suggests that complex molecules known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) play a primary role in absorbing light. Just how these molecules affect our overall view of the cosmos will be a focus of future study.

Reference: Zhang, Xiangyu, and Gregory M. Green. “Three-dimensional maps of the interstellar dust extinction curve within the Milky Way galaxy.” Science 387.6739 (2025): 1209-1214.