As summer temperatures soar, a dip can seem like a great way to cool off. But it can be hard to know if the water at the nearby beach or river is clean enough for swimming. Images from space may someday provide answers.

An instrument aboard the International Space Station can “see” sewage thanks to a discovery that the contamination absorbs certain wavelengths of light, researchers report in the June 15 Science of the Total Environment.

Usually, water from swimming spots is tested for sewage contamination by measuring harmful bacteria levels. These tests are conducted at only a few sampling points, though, so contamination in other areas might get missed. Viewing the entire body of water at once could help solve this problem.

Images from space offer a potential solution — they are already used to track snowmelt, wildfires and algal blooms. But only things that interact with light can be seen in these images, says Daniel Maciel, a geospatial researcher at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research in São José dos Campos who was not involved in the study. Sewage bacteria don’t usually do that, he says. So how can sewage be seen from space?

Previous studies have looked at things like roughness of the water surface, but oceanographer Eva Scrivner took a different approach. She and colleagues collected sewage samples from a wastewater treatment plant in San Diego. “I was basically pouring poop into cups,” says Scrivner, who was at San Diego State University at the time.

Back in the lab, she put the samples under a tungsten light bulb. Analyzing the illuminated samples with a spectrometer, she noticed that the more sewage bacteria the water had, the more it absorbed particular wavelengths of orange light.

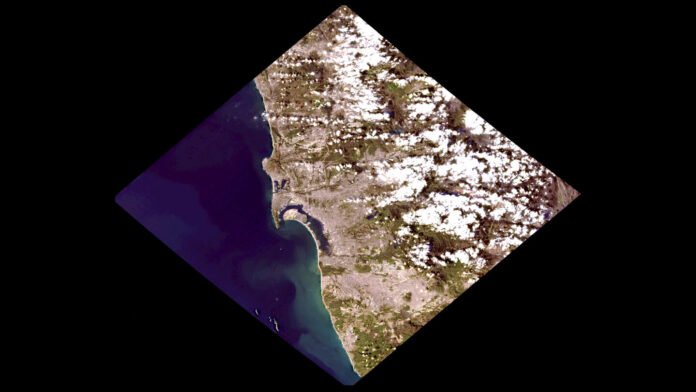

This same decrease in orange light turned up in images of a known sewage stream coming from the Tijuana River into San Diego’s Imperial Beach taken by EMIT, an imaging spectrometer aboard the space station. Measurements of this orange wavelength functioned like a “color scale,” showing how much sewage was in the water.

Only parts of the United States are visible to EMIT from the ISS, and the space station doesn’t revisit the same spot at consistent time intervals. But an upcoming NASA mission, a space-based instrument called GLIMR, which will be focused in part on the U.S. coasts and the Gulf of Mexico, may also be able to pick up the same sewage signature.

The change in water color might be caused by cyanobacteria growing in the sewage, says coauthor Christine Lee, a geospatial researcher at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Maciel cautions that cyanobacteria grow in clean water too, so this method would need to be validated in other water sources where it might be used. But in waters where the color scale is associated with sewage, these space snapshots could take the guesswork out of choosing which locations to sample for testing, says Scrivner, who is now at the University of Connecticut in Groton. That could mean the difference between a nice day at the beach or going home with a stomachache.

Source link