The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) has learned to do backward rolls to give its onboard radar better opportunities to find water-ice beneath the red planet’s surface.

“Not only can you teach an old spacecraft new tricks, you can open up entirely new regions of the subsurface to explore by doing so,” Gareth Morgan of the Planetary Science Institute and co-investigator on MRO’s Shallow Radar (SHARAD) instrument, said in a statement.

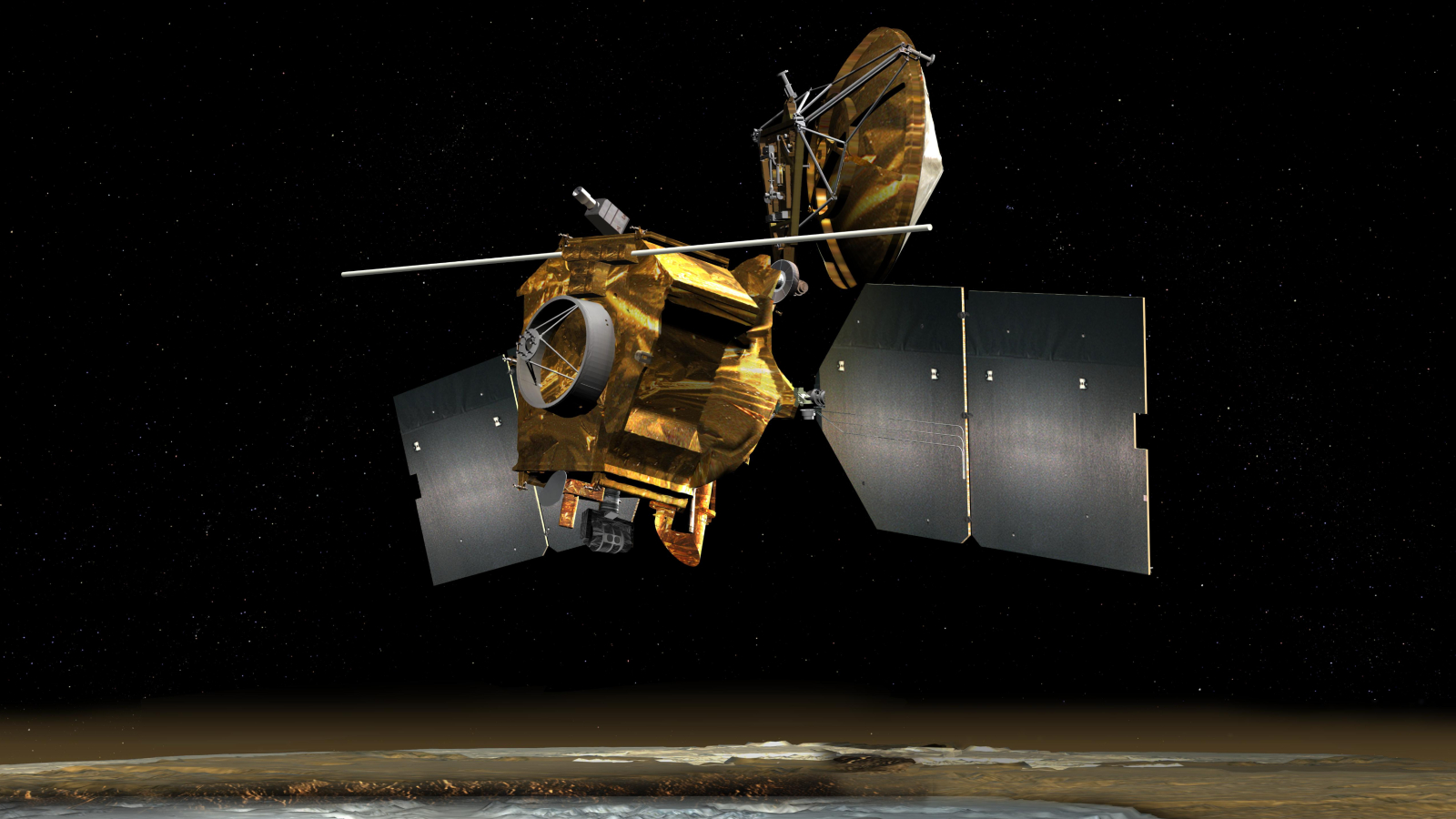

MRO is something of a veteran now, having been in orbit around Mars since 2006. It carries five instruments still in operation (a sixth, the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, CRISM, was shut down in 2023). The spacecraft typically points these instruments at targets on the surface by tipping itself over by up to 28 degrees. If MRO performs one of these rolls so a particular instrument can get a good view of something, it usually means the other four are inconvenienced, hence why the roll maneuvers are planned weeks in advance so as not to interrupt other observations.

Things usually work out — however, the SHARAD instrument has always been at a disadvantage.

SHARAD fires pulses of radar at Mars that are able to detect water-ice buried as deep as 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) below the surface. Yet, SHARAD is positioned on the rear of the spacecraft, playing second fiddle to the likes of the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), which has the best views in the house from the front of the spacecraft. From the rear, SHARAD’s radar beams typically catch part of the spacecraft’s structure, resulting in interference that reduces clarity and how deep underground it can probe.

“The SHARAD instrument was designed for the near-subsurface and there are select regions of Mars that are just out of reach for us,” said Morgan. “There is a lot to be gained by taking a closer look at those regions.”

So, starting in 2023, MRO’s engineers began experimenting with the spacecraft by performing what they describe as “very large rolls” of 120 degrees, spinning the spacecraft backwards so it is almost upside down relative to Mars. During the large roll, SHARAD gets an unencumbered view of Mars’ surface, which permits the radar signal to be 10 times stronger.

There is a caveat to these very large rolls, though. During a standard roll of up to 28 degrees, MRO’s high-gain antenna can remain pointed at Earth and its solar arrays can keep tracking the sun to maintain power. During a 120-degree roll, the high-gain antenna isn’t pointed at Earth and the solar arrays lose sight of the sun.

This means that a 120-degree roll requires even more planning before it is performed.

“The very large rolls require a special analysis to make sure we’ll have enough power in our batteries to safely do the roll,” Reid Thomas, who is MRO’s Project Manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in the statement.

As a result, the MRO team is limiting the spacecraft to just one or two very large rolls each year, but they hope to be able to streamline the process and perform these maneuvers more often in future. It could really be worth it: Finding large pockets of water-ice close to the Martian surface would be vital for future astronauts who could use it for drinking water as well as for producing oxygen and rocket fuel. Plus, the very existence of the water at different latitudes can tell us more about the history of water and the past climate of Mars.

There’s also another benefit to the rolls. There is one instrument on MRO that was not designed to require rolls to point, and that is the Mars Climate Sounder, which measures small changes in temperature over the course of the Martian seasons. The Climate Sounder has to be able to point both down at the surface and at the horizon where it can peer through the thin layers of Mars’ atmosphere; to aid it in these observations, the Climate Sounder was affixed to its own gimbal. However, by 2024, this gimbal had grown unreliable due to age, and so the Climate Sounder now relies on the standard 28-degree rolls to make its observations. The very large 120-degree rolls give the Climate Sounder more flexibility.

Where it used to be the case that the rolls limited MRO’s science output because they only gave a good view to one instrument at a time, the rolls are now helping the aging Mars probe to maintain its science output. It’s not quite cartwheels, but it shows that MRO still has a lot of life left in it yet.

An assessment of the success of the large rolls is described in The Planetary Science Journal.