There was a glimmer in the air tonight at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, and it wasn’t only because a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket took to the skies carrying precious NASA cargo.

As the agency’s SPHEREx space telescope and PUNCH solar mission rode toward their orbital stations tonight (March 11) at 11:10 p.m. EST (0310 March 12 GMT), members of mission control appeared elated, onlookers who caught a peek at the liftoff cheered, and the scientists who built these missions exuded a blend of relief and excitement.

“I am so happy that we’re finally in space!” said Farah Alibay, the lead flight system engineer on SPHEREx at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “It feels really great to have SPHEREx in space.”

This launch follows an unexpected string of several delays, unfortunate setbacks such as the devastating California wildfires that affected several mission members, and general turmoil at the agency that has been making headlines recently. And, additionally, the combined promise of SPHEREx and PUNCH is huge, both metaphorically and literally. (The integrated SPHEREx and PUNCH stack weighed around 1,667 pounds, or 756 kilograms).

What is SPHEREx?

Some of the anticipation surrounding the $488 million SPHEREx mission mirrors what we saw on Christmas Day in 2021, when scientists launched the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) toward its spaceborne destination of Lagrange Point 2 — and for good reason.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope images: 16 astonishing views of our universe (gallery)

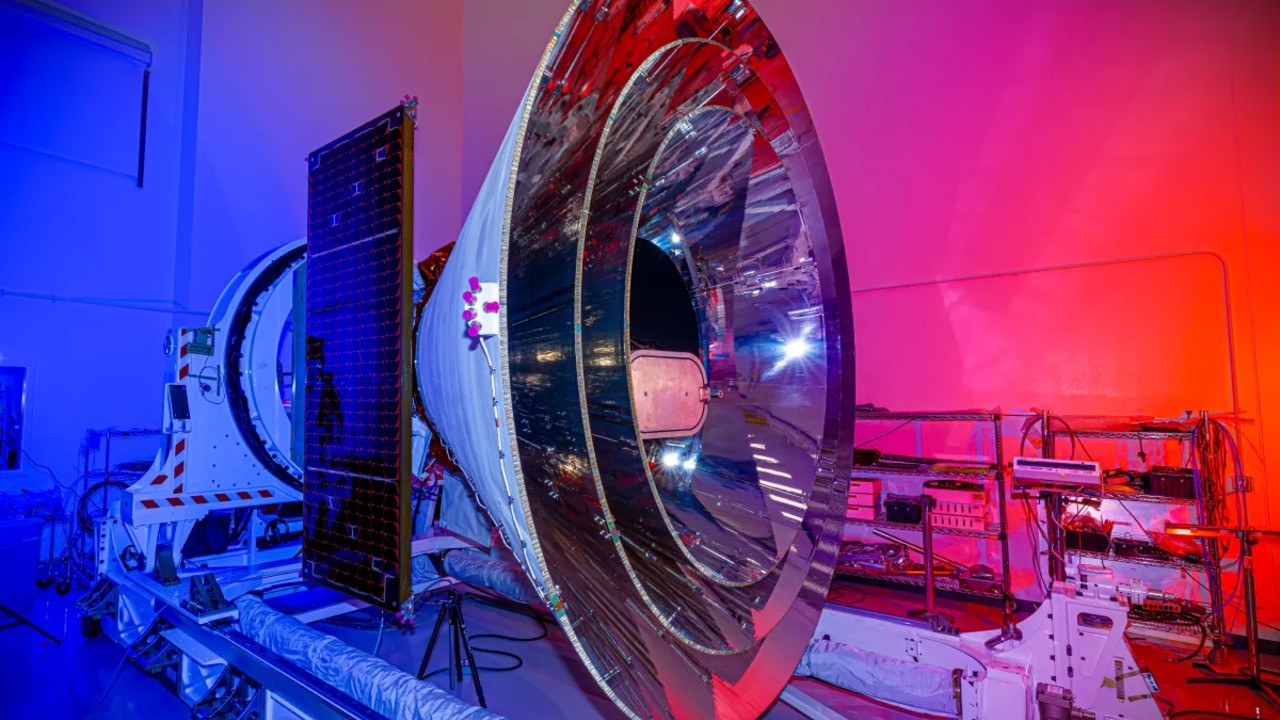

Like the JWST, SPHEREx — which stands for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer — works with infrared wavelengths, which are invisible to human eyes. They’re more akin to heat signatures; firefighters, for instance, use infrared wavelength detectors when figuring out where fires are concentrated in a target building.

The reason astronomers care about infrared wavelengths, however, has to do with the fact that the universe has been expanding since the beginning of time. This expansion affects light wavelengths emanating from cosmic objects of interest, like stars, that travel toward our detectors on Earth. Once tighter, blueish wavelengths can stretch out like rubber bands to become longer, reddish ones — and when traveling across vast distances, those wavelengths can really stretch out to end up in the infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum. All in all, this means light coming from faraway objects is invisible to human eyes and the bulk of human technology.

The JWST and SPHEREx, however, can indeed collect data from those wavelengths. This fascinatingly gives us a window into a section of the universe typically hidden to us.

Other telescopes, to be fair, have had infrared abilities, such as the now-retired Spitzer telescope and even the Hubble Space Telescope, but not quite enough to match up to the prowess of the JWST and SPHEREx. There are other benefits of infrared wavelengths too; for instance, they can help scientists see behind blankets of dust covering budding stars and decode intricacies of exoplanetary atmospheres.

Related: Exoplanets: Everything you need to know about the worlds beyond our solar system

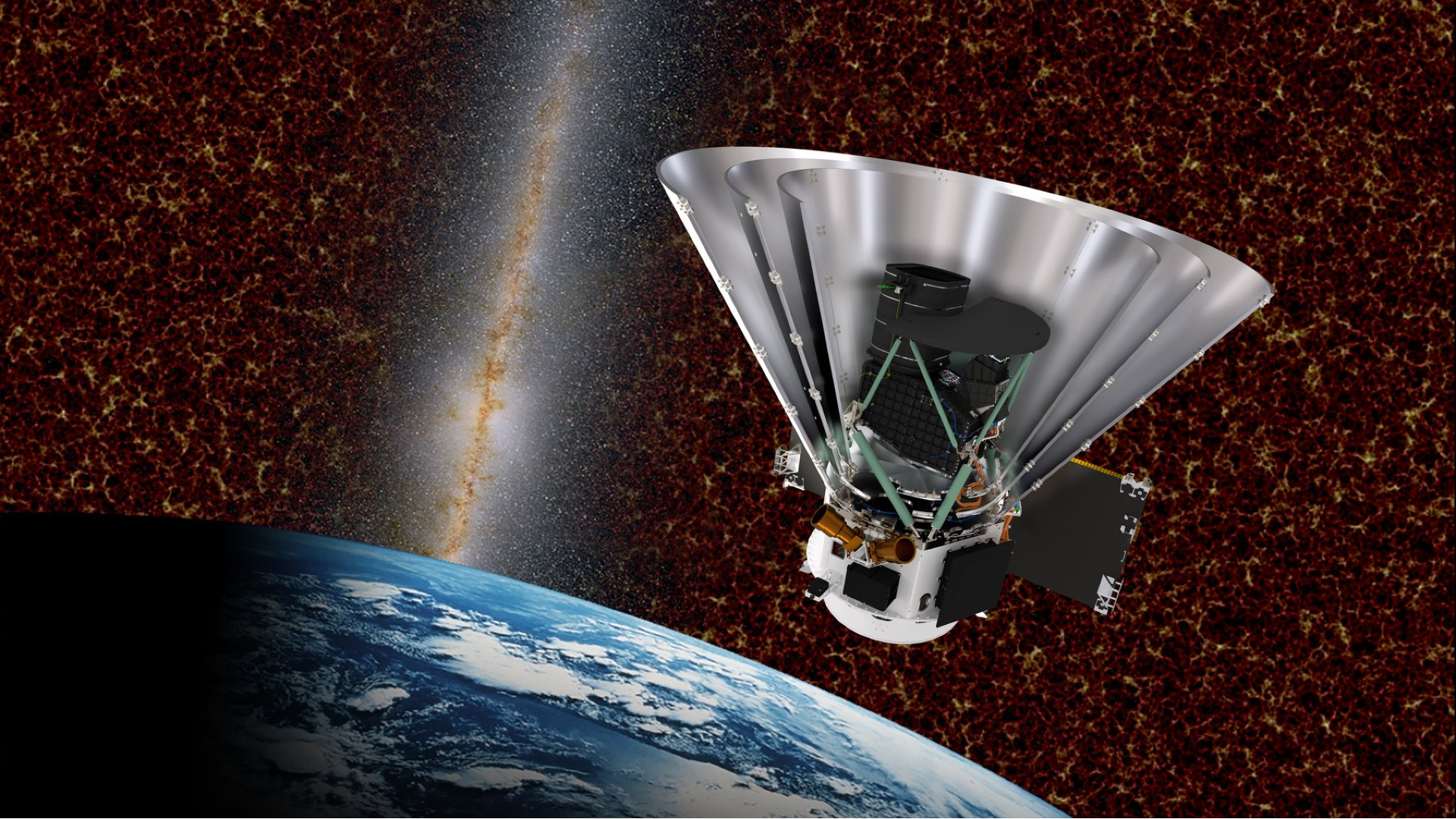

There is a difference between the JWST and SPHEREx, though — a key one. The JWST is more adept at creating extremely dimensional views of small sections of sky, while the 8.5-foot-tall (2.6-meter), conical SPHEREx telescope is built to take a more wide-field approach. “We are literally mapping the entire celestial sky in 102 infrared colors for the first time in humanity’s history,” Nicky Fox, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said during a conference about the mission on Jan. 31.

As the mission team puts it, it’s “like scanning the inside of a globe.”

The next steps for SPHEREx, now that it has entered space, involve successfully traveling to its selected orbit — a polar orbit that’s “sun-synchronous,” which means the spacecraft’s position relative to the sun remains consistent. This kind of orbit is important for the mission because SPHEREx must be kept protected from the sun’s heat at all times; recall how infrared wavelengths are like heat signatures. Heat interference would seriously mess up the telescope’s data (the JWST’s L2 station is also perfectly protected from solar heat).

“By remaining over Earth’s day-night (or terminator) line for the entire mission, the observatory will keep the conical photon shields that surround its telescope pointed at least 91 degrees away from the sun,” a mission overview states.

Plus, as NASA explains in that mission overview, the telescope will need to point away from Earth as well because of our own planet’s bright infrared glow. Then, once safe: “Each approximately 98-minute orbit allows the telescope to image a 360-degree strip of the celestial sky. As Earth’s orbit around the sun progresses, that strip slowly advances, enabling SPHEREx to complete an all-sky map within six months.”

And while we’re on the topic of the sun, it’s time to pivot to PUNCH.

What is PUNCH?

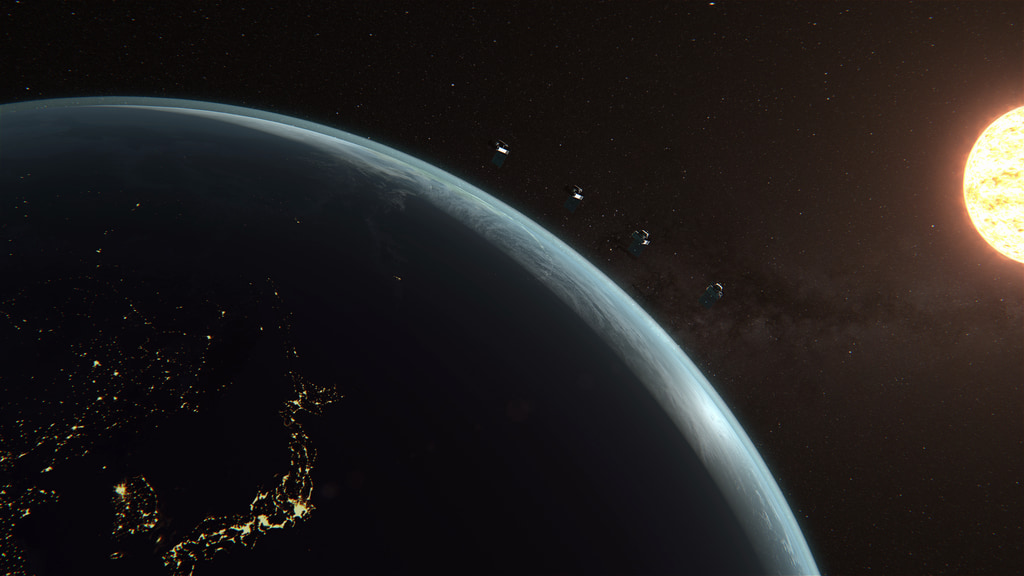

The $165 million PUNCH mission, by contrast, was constructed to literally zero in on the sun. It stands for Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere and, more specifically, is meant to decode how the sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona, turns into the solar wind.

The thing is, we kind of live within a solar wind chamber, a bubble that encapsulates our solar system called the heliosphere, but scientists aren’t quite sure of the exact dynamics within this sphere. It is, however, quite important to understand such dynamics because it can help with goals like improving space weather forecasts, which directly impact our safety here on Earth.

Space weather, which typically stems from bursts of plasma erupting off the sun in the form of coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, can create blips in our power grid, interrupt GPS signals, pose threats to astronauts in space (and, to add some bittersweetness, generate glowing auroras around our planet).

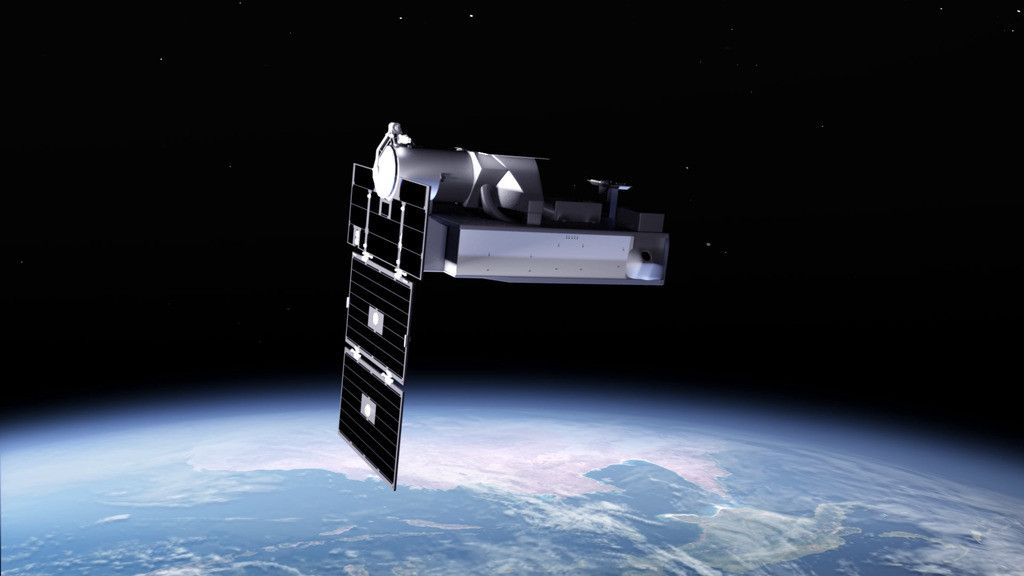

The PUNCH mission involves four little 140-pound (63.5-kg) satellites, three of which are wide-field imagers and one of which is a narrow-field imager. The narrow-field imager is essentially going to be able to mimic a total solar eclipse for itself — except on another level.

Recall what the natural 2024 total solar eclipse looked like: a hazy white halo around a dark circle. The white halo was the sun’s corona, and the dark circle was the moon’s silhouette. It’s the same idea — PUNCH’s narrow-field imager can generate an artificial solar eclipse, except this artificial eclipse will be visible 24-7 and the corona will appear in much higher definition.

The wide-field imagers, meanwhile, are meant to call on a concept called polarimetry — which you can read about in far more depth here — in order to create a super detailed, 3D map of features seen throughout the sun’s corona and the inner solar system. That includes CMEs, of course.

“We have to have two kinds of instruments,” Craig DeForest, PUNCH’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute, told reporters on Feb. 4. “One that looks close to the sun, where it’s bright, and one that looks farther from the sun where it’s fainter.”

The four PUNCH satellites will also sit in a polar, sun-synchronous orbit near Earth’s day-night line — but ironically, unlike its carpool partner SPHEREx, PUNCH will always be in sunlight.

Rocket stuff and beyond

Launch, it seems, went without a hitch — a win for NASA’s relatively new Launch Services Program, which aims to match space missions with appropriate vehicles to cut down on costs and maximize efficiency (the reason behind SPHEREx and PUNCH’s carpool situation).

However, the story is far from over.

Both PUNCH and SPHEREx need to settle into their respective orbits, one hidden from the sun and other basking in it, and after that scientists will still need to boot up the spacecraft’s equipment to make sure there aren’t any issues.

As of now, the PUNCH mission is scheduled to conduct science for at least two years, the mission team says, following a 90-day commissioning period that starts tonight. SPHEREx, on the other hand, is expected to collect data about over 450 million galaxies along with more than 100 million stars in the Milky Way over a two-year planned mission.

When all is looking good, it’ll certainly be a joy to welcome two new members to our metal space explorer feat. Surely, the Parker Solar Probe will be inviting PUNCH to sit at its lunch table while the JWST and SPHEREx will be hanging out in the halls.