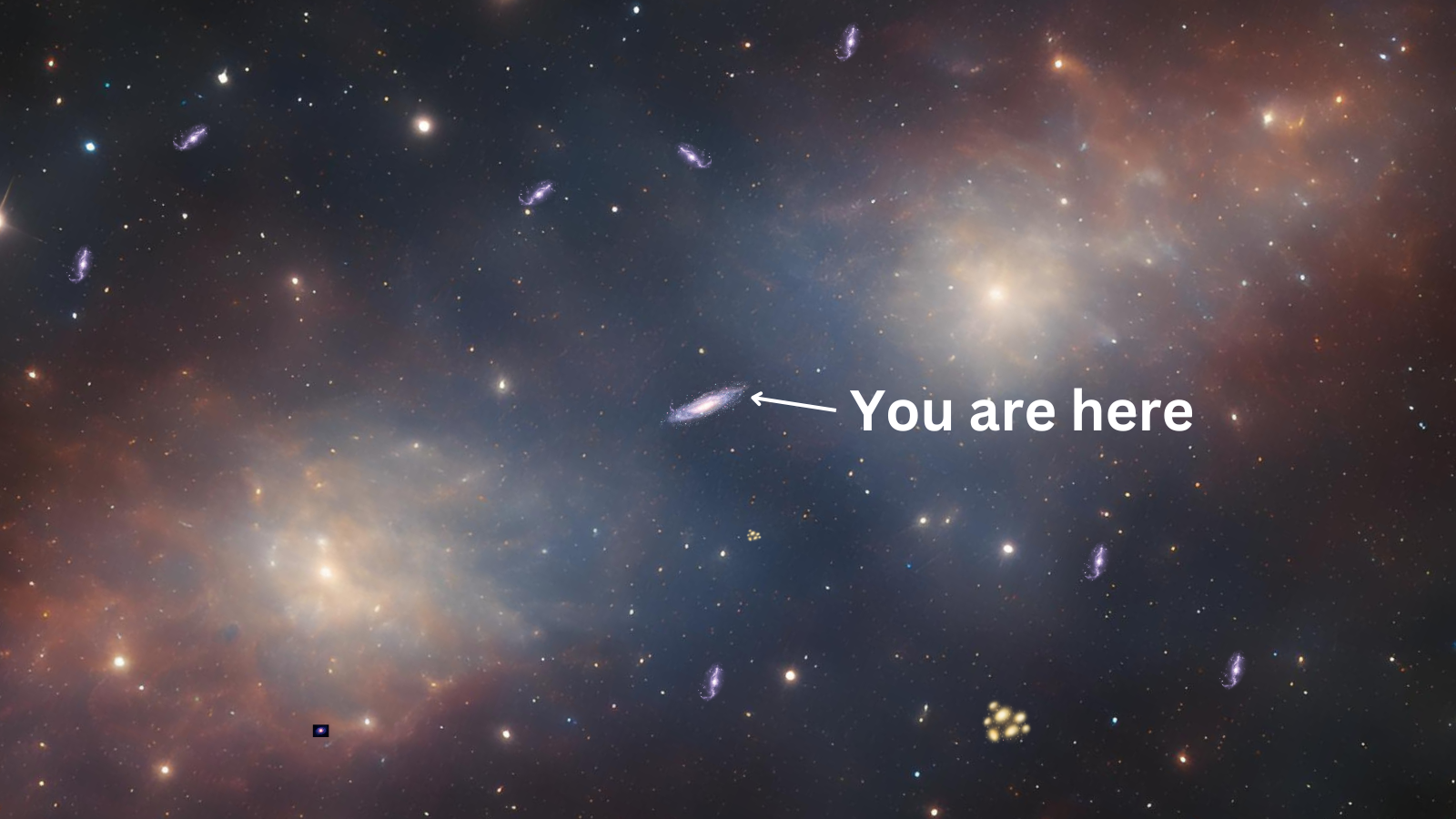

Earth, its cosmic home the Milky Way, and even the very local region of universe around us could be situated within a void of low density compared to the rest of the universe.

If so, that would solve one of the most frustrating and lingering problems in cosmology, the so-called “Hubble tension.”

New research suggests that “baryon acoustic oscillations (BAOs)” from the initial moments of the universe, think of them as “the sound of the Big Bang,” seem to support the concept of the local void or “Hubble Bubble.”

The Hubble tension arises from the fact that when measured using different techniques the speed at which the universe is expanding (known as the Hubble constant) has different values. One technique measures the Hubble constant using astronomical observations in the local universe, while the other gives its value as an average across the entire universe.

That means if the local universe sits in a low-density “Hubble bubble,” it would be expanding faster than the higher-density wider cosmos, explaining why observations give a larger Hubble constant value and faster expansion than slower theoretical averages.

“A potential solution to this inconsistency is that our galaxy is close to the center of a large, local void,” research author Indranil Banik of the University of Portsmouth said in a statement. “It would cause matter to be pulled by gravity towards the higher density exterior of the void, leading to the void becoming emptier with time.

“As the void is emptying out, the velocity of objects away from us would be larger than if the void were not there. This, therefore, gives the appearance of a faster local expansion rate.”

Hubble tension: A ‘local problem’?

There are two ways to calculate the Hubble tension.

For one, scientists observe a “cosmic fossil” called the cosmic microwave background (CMB). The first light that was free to travel the universe, the CMB, is a field of radiation that almost evenly and uniformly fills the entire cosmos.

Scientists can observe the CMB and calculate its evolution using the Lambda Cold Dark Matter model (LCDM), the standard model of cosmology, as a template. From this, they derive the current-day value for the Hubble constant across the universe as a while, not just locally.

Alternatively, astronomers use observations of type Ia supernovas or variable stars, two examples of objects that astronomers call “standard candles,” to measure distances to their host galaxies. How fast these galaxies are receding is revealed by the change in the wavelengths of light from these bodies, or the “redshift.” The bigger the redshift, the faster a galaxy moves away from Earth. The Hubble constant can be calculated from this.

The problem is that this observation method of the local universe gives a Hubble Constant value that is greater than the theoretical value obtained with the Lambda CDM, which considers the universe as a whole. Hence the Hubble tension.

Banik thinks that this discrepancy is a local problem.

“The Hubble tension is largely a local phenomenon, with little evidence that the expansion rate disagrees with expectations in the standard cosmology further back in time,” Banik said. “So, a local solution like a local void is a promising way to go about solving the problem.”

For this local void theory to solve the Hubble tension, Earth and the solar system would have to sit roughly centrally within the low-density Hubble bubble. The Hubble bubble would have to be around 2 billion light-years wide, with a density around 20% lower than the universe’s average matter density.

Indeed, counting the number of galaxies in the local universe does seem to reveal a lower density than neighboring parts of the cosmos.

However, a major stumbling block to this concept is the fact that the existence of such a vast void doesn’t fit well with the LCDM, which suggests matter should be evenly spread in all directions, or “isotropically and homogenously” distributed through the universe.

New data obtained by Banik shows that the sound of the Big Bang, known as Baryon Acoustic Oscillations or BAOs, actually support the concept of a local void contrary to the LCDM.

“These sound waves traveled for only a short while before becoming frozen in place once the universe cooled enough for neutral atoms to form,” Banik explained. “They act as a standard ruler, whose angular size we can use to chart the cosmic expansion history.”

Banik argues that a local void slightly distorts the relation between the BAO angular scale and the redshift. This is because velocities induced by a local void and its gravitational effect slightly increase the redshift in addition to that caused by cosmic expansion.

“By considering all available BAO measurements over the last 20 years, we showed that a void model is about one hundred million times more likely than a void-free model with parameters designed to fit the CMB observations taken by the Planck satellite, the so-called homogeneous Planck cosmology,” Banik added.

The next step for Banik and colleagues will be to compare their void model to other models to try to reconstruct the universe’s expansion history.

This could involve the use of “cosmic chronometers,” massive evolving cosmic objects like galaxies that can be aged to determine how the rate of expansion of the universe has changed over time. With galaxies, this can be done by observing stellar populations and seeing what type of stars they possess, with an absence of shorter-lived massive stars indicating a more advanced age.

This age is then compared with the redshift the galaxy’s light has undergone as a result of the expansion of the universe as it traveled to us, revealing the expansion history of the universe over cosmic time.

Perhaps this way, the headache of Hubble tension can be relieved permanently.

The team’s research was presented by Banik on Monday (July 7) at the Royal Astronomical Society National Astronomy Meeting (NAM) 2025 at Durham University in the UK.